Thursday, November 3, 2011

Postscript

Dad left for the next mission on August 13, 2010. He lived a heck of a life in his 89 years. He always thought of himself as one of the luckiest people who ever lived. It's hard to argue with that.

Wednesday, May 9, 2007

Added Thanks

Thanks to those of you who have come online to read this memoir.

Notably, to our friend John Berry, who has more knowledge and interest than most of our generation of the activities in the Pacific during the war. Thanks, John, for helping pass this stuff down.

Special thanks to Merlin Dorfman, for his corrections and addenda. Merlin, quite the WWII scholar, sent along some material I hope to be adding to comments from the appropriate posts soon.

Also thanks to our dear friend Tess Cowie for her kind words. Tess's husband Bill was a retired Marine Major who served his own brave time in the war. Bill and Dad had an longtime,ongoing, good-natured ideological debate, Dad the Sailor, Bill the Marine; Dad the Democrat, Bill the Republican. It's a debate that Dad has always truly relished, in which he's found many counterparts, probably none as well-suited as Bill.

Ed

Notably, to our friend John Berry, who has more knowledge and interest than most of our generation of the activities in the Pacific during the war. Thanks, John, for helping pass this stuff down.

Special thanks to Merlin Dorfman, for his corrections and addenda. Merlin, quite the WWII scholar, sent along some material I hope to be adding to comments from the appropriate posts soon.

Also thanks to our dear friend Tess Cowie for her kind words. Tess's husband Bill was a retired Marine Major who served his own brave time in the war. Bill and Dad had an longtime,ongoing, good-natured ideological debate, Dad the Sailor, Bill the Marine; Dad the Democrat, Bill the Republican. It's a debate that Dad has always truly relished, in which he's found many counterparts, probably none as well-suited as Bill.

Ed

Saturday, April 21, 2007

Forward

The following series of posts comprise a memoir my father, Jim Nicholson, wrote about the first twenty-eight years of his life.

If you read it, you'll see the majority of it concerns his time in the Navy; much of it about service in the Pacific during World War II. Most of Dad's memories here were reinforced by log books he kept as a radioman/ tail gunner on a torpedo plane (TBF), flying off aircraft carriers.

I've had this memoir since he wrote it in the mid-90's. I'd read it a couple of times, but was recently asked to show it to a journalist writing a story about those who served during that war. In re-reading it this time, I found the stories much more compelling than before. Perhaps because telling these stories seems to come easier to Dad now than it did earlier in my life, so this account provides detail, texture, timeline and context to some of what I've heard in more recent years. Perhaps because it's easy to realize that the opportunity to hear firsthand accounts of life in America during the first half of the twentieth century are becoming rarer every day. Perhaps it's because I'm now a father myself, and only now can truly appreciate the hard work and sacrifices of my father, my mother, and many, many more of their generation, who have made their children's lives much easier than their own.

I post this as a tribute to my folks and an archive of their stories. If you or someone you know or love find something of relevance here, I welcome your comments, corrections, additions, and personal stories.

Ed

If you read it, you'll see the majority of it concerns his time in the Navy; much of it about service in the Pacific during World War II. Most of Dad's memories here were reinforced by log books he kept as a radioman/ tail gunner on a torpedo plane (TBF), flying off aircraft carriers.

I've had this memoir since he wrote it in the mid-90's. I'd read it a couple of times, but was recently asked to show it to a journalist writing a story about those who served during that war. In re-reading it this time, I found the stories much more compelling than before. Perhaps because telling these stories seems to come easier to Dad now than it did earlier in my life, so this account provides detail, texture, timeline and context to some of what I've heard in more recent years. Perhaps because it's easy to realize that the opportunity to hear firsthand accounts of life in America during the first half of the twentieth century are becoming rarer every day. Perhaps it's because I'm now a father myself, and only now can truly appreciate the hard work and sacrifices of my father, my mother, and many, many more of their generation, who have made their children's lives much easier than their own.

I post this as a tribute to my folks and an archive of their stories. If you or someone you know or love find something of relevance here, I welcome your comments, corrections, additions, and personal stories.

Ed

Medals and Commendations

We've received a good suggestion that we post a list of the medals and commendations that were awarded to Dad and the units he was in for their service.

Distinguished Flying Cross

Air Medal Gold Stars in Lieu of Second and Third Air Medals

Presidential Unit Citation with Gold Star

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with Six Battle Stars

Good Conduct Medal

WWII Victory Medal

Distinguished Flying Cross

Air Medal Gold Stars in Lieu of Second and Third Air Medals

Presidential Unit Citation with Gold Star

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with Six Battle Stars

Good Conduct Medal

WWII Victory Medal

Prologue

The purpose for this writing is to clarify and to put into proper sequence some of the events which I have experienced in my lifetime, for the benefit of my children and grandchildren.

Although my sons have probably already heard most of the things that I shall put to writing, I have never had the time to go into them in any detail, nor have they been-told in any proper chronological sequence, I have always been known as the world's poorest writer, so nothing I say will surprise anyone.

Although my sons have probably already heard most of the things that I shall put to writing, I have never had the time to go into them in any detail, nor have they been-told in any proper chronological sequence, I have always been known as the world's poorest writer, so nothing I say will surprise anyone.

Early Memories--Growing Up in Harrison 1921-1933

I was born December 25th, 1921 in Harrison, Arkansas at the corner of South Maple Street and West Newman Avenue; the fourth child of William Newton and Mabel Womack Nicholson. Dr. Frank Kirby was the attending doctor; and, of course, at that time there were no clinics or hospitals in Boone County.

The first memory of my childhood was waking up to the crowing of the neighborhood roosters when I was about two years of age. Harrison was a hamlet of about fifteen hundred people at that time, and my father ran a partnership general mercantile business with my Uncle Roy and Granddad Amzi Nicholson. The business was located on the south side of the square and 'that was before there was any paving, sidewalks (concrete) and curbing around the square.

Another early memory is of the neighborhood children and my older brother and sisters playing doctors and nurses, and using me as their patient in performing a tonsillectomy. They didn't hurt me, but I remember that they scared me to death for the fact that I thought the baling wire instrument was going to be stuck down my throat. I am sure that I screamed and mother came running to the rescue.

Another memory of that early period was that one night my brother, Eugene had the whole neighborhood looking for him. Gene was about eight years old, and when the folks discovered that he was missing from his bed, they searched the entire neighborhood, with the help of most of them., to no avail. The next morning at daylight, he came walking out of one of our neighbor's woodsheds. He had been delirious with fever the night before, and had walked in his sleep to a newfound bedroom. He was all right and had no ill effects from his venture, but it surely did scare Mom and Dad.

When I was about three years old, Dad sold his interest in the store business to Uncle Roy and Grandpa Amzi, and we moved to my Grandma Womack's farm south of town. Dad started a small dairy operation and was milking 15 to 20 Jersey cows by hand twice a day. He would bottle the milk, load it onto a buggy, and deliver it to people around town. Although Gene was only nine or ten years old, he would help milk, but Dad really had his hands full. The dairy business lasted Dad about three years and he decided to sell out the herd and move-back to town.

In 1928, after we moved to town, Dad bought the American Cafe, which was about half a block off the square on East Stephenson Avenue. By this time, we children, all five of us, were enrolled in school, and we were living on North Maple Street. Uncle Roy was still operating the store, and he and Uncle Riley Womack (the painter) made me a shoe box and stocked it with polish and brushes and I would spend the summer shining shoes in the courtyard for 5 cents per pair. This was when I was from seven to nine years old and I could save enough nickels to help Dad pay my school tuition and buy school supplies. In addition to shining shoes, boys could earn spending money by gathering up burlap sacks and selling to the feed stores for reuse, gathering used medicine bottles and selling to the drug stores for reuse and gathering aluminum and copper wire and selling to the salvage yards. By either of these enterprises or by running errands and doing lawn work and odd jobs, we could make our spending money for the Saturday afternoon "shoot'em up" and the continued serial which we could not afford to miss.

In 1930-31, Dad had sold the cafe and was working for the city as night watchman on the police force. About this time, my Uncle Hubert Brown started Lone Oak Dairy in partnership with his brother, Carl, who worked also for the railroad. He gave me the job of bouncing on the milk truck. I would ride the fender, except when we had falling weather, and place the milk on the porches and pick up the empty bottles, while he drove the truck on the milk route. I did this until I was about fourteen years old. I had to quit because I developed a limp from jumping off the truck and Dr. Henry Kirby said I would become a permanent cripple if I continued. Hubert sold the milk for 10 cents per quart then and he paid me 10 cents at night and 15 cents in the morning for helping him deliver. During the depression, in the thirties, pennies looked as big as dollars now. In about 1932, Dad was no longer working for the city as a policeman and he was glad to do any kind of work he could find for ten or fifteen cents an hour. He always raised a huge garden and he would work it before and after any other work that he could find. I do not ever remember a day that he did not work from literally daylight until dark. He could never earn enough to supply his children with any luxuries but with us children helping to buy our clothing, he supplied the food and shelter and for a family of seven in that day and time, that was a lot. In 1933, he got a job as a day laborer on the WPA making twenty five cents an hour helping to build the old levee along South Spring Street and down Central Avenue between the creek and the square. In the fall of 1933, my sister, Evangelyn, who was eighteen months younger than I, became ill with rheumatic fever. There were no clinics or hospitals in Harrison then, so mother had to nurse her at home. I spent the winter with my Uncle Riley and Grandmother Womack because mother and my two older sisters had their hands full taking care of my baby sister. There was very little that could be done for her medically, and she developed a leakage of the heart and died the following spring.

Uncle Roy had gone broke in the store business in 1931 and had started operating a company owned service station on the corner of Cherry and Stephenson arid Aunt Mittie had a little lunchroom adjoining called The Goblin's Den. This was just across the street from the high school and Central grade school, so in addition to Aunt Mittie selling hamburgers, chili, candy and school supplies in the Goblin's Den, Roy also had the concession to sell candy, popcorn, gum and soft drinks at all of the athletic events both in the gymnasium and the football field. So, he gave me the job of helping him sell from the concession stands at the ballgames. Dad was also helping Uncle Roy with the service station work, and I would also help at that part of the time, I remember that we sold hand pumped gasoline for as low-as eleven. cents per gallon, kerosene for seven cents a gallon, motor oil in bulk for ten cents a quart, flats repaired and grease jobs for a quarter and batteries charged for twenty nine cents. Business got so good for the Southland Cut Rate Station that Roy was operating, that in 1935, they decided to build another one; so they built the station that is on the right of the highway on the curve at the south end of the Krooked Kreek bridge and hired Dad to operate it for them. By this time I was in junior high school and was helping Dad in the station what time I was not in school. Dad operated the station for Southland until in 1938, when he went to work for the Arkansas Highway Department, helping to service and maintain their vehicles and road equipment. I worked about a year part time for Paul Lee, who was operating the Barnsdall service station on the corner of Stephenson and Pine Streets, when I was a sophomore in high school.

I guess you would think that I had no time for playing while I was growing up? Not so!!! We lived along the banks of Krooked Kreek, and we spent a lot of time swimming and fishing and even skating on its ice in extremely cold weather. Yoyos, tops, marbles, horseshoes, shinney, rubber guns, beanflips, hoops and tire rolling, football, baseball, and basketball and track events were all inexpensive ways of having fun and we never had any trouble of finding plenty of playmates to participate in any and all activities. Oh yes, there was also horseback riding, bicycling and tennis. I had a pony until I was eight or nine years old.

The first memory of my childhood was waking up to the crowing of the neighborhood roosters when I was about two years of age. Harrison was a hamlet of about fifteen hundred people at that time, and my father ran a partnership general mercantile business with my Uncle Roy and Granddad Amzi Nicholson. The business was located on the south side of the square and 'that was before there was any paving, sidewalks (concrete) and curbing around the square.

Another early memory is of the neighborhood children and my older brother and sisters playing doctors and nurses, and using me as their patient in performing a tonsillectomy. They didn't hurt me, but I remember that they scared me to death for the fact that I thought the baling wire instrument was going to be stuck down my throat. I am sure that I screamed and mother came running to the rescue.

Another memory of that early period was that one night my brother, Eugene had the whole neighborhood looking for him. Gene was about eight years old, and when the folks discovered that he was missing from his bed, they searched the entire neighborhood, with the help of most of them., to no avail. The next morning at daylight, he came walking out of one of our neighbor's woodsheds. He had been delirious with fever the night before, and had walked in his sleep to a newfound bedroom. He was all right and had no ill effects from his venture, but it surely did scare Mom and Dad.

When I was about three years old, Dad sold his interest in the store business to Uncle Roy and Grandpa Amzi, and we moved to my Grandma Womack's farm south of town. Dad started a small dairy operation and was milking 15 to 20 Jersey cows by hand twice a day. He would bottle the milk, load it onto a buggy, and deliver it to people around town. Although Gene was only nine or ten years old, he would help milk, but Dad really had his hands full. The dairy business lasted Dad about three years and he decided to sell out the herd and move-back to town.

In 1928, after we moved to town, Dad bought the American Cafe, which was about half a block off the square on East Stephenson Avenue. By this time, we children, all five of us, were enrolled in school, and we were living on North Maple Street. Uncle Roy was still operating the store, and he and Uncle Riley Womack (the painter) made me a shoe box and stocked it with polish and brushes and I would spend the summer shining shoes in the courtyard for 5 cents per pair. This was when I was from seven to nine years old and I could save enough nickels to help Dad pay my school tuition and buy school supplies. In addition to shining shoes, boys could earn spending money by gathering up burlap sacks and selling to the feed stores for reuse, gathering used medicine bottles and selling to the drug stores for reuse and gathering aluminum and copper wire and selling to the salvage yards. By either of these enterprises or by running errands and doing lawn work and odd jobs, we could make our spending money for the Saturday afternoon "shoot'em up" and the continued serial which we could not afford to miss.

In 1930-31, Dad had sold the cafe and was working for the city as night watchman on the police force. About this time, my Uncle Hubert Brown started Lone Oak Dairy in partnership with his brother, Carl, who worked also for the railroad. He gave me the job of bouncing on the milk truck. I would ride the fender, except when we had falling weather, and place the milk on the porches and pick up the empty bottles, while he drove the truck on the milk route. I did this until I was about fourteen years old. I had to quit because I developed a limp from jumping off the truck and Dr. Henry Kirby said I would become a permanent cripple if I continued. Hubert sold the milk for 10 cents per quart then and he paid me 10 cents at night and 15 cents in the morning for helping him deliver. During the depression, in the thirties, pennies looked as big as dollars now. In about 1932, Dad was no longer working for the city as a policeman and he was glad to do any kind of work he could find for ten or fifteen cents an hour. He always raised a huge garden and he would work it before and after any other work that he could find. I do not ever remember a day that he did not work from literally daylight until dark. He could never earn enough to supply his children with any luxuries but with us children helping to buy our clothing, he supplied the food and shelter and for a family of seven in that day and time, that was a lot. In 1933, he got a job as a day laborer on the WPA making twenty five cents an hour helping to build the old levee along South Spring Street and down Central Avenue between the creek and the square. In the fall of 1933, my sister, Evangelyn, who was eighteen months younger than I, became ill with rheumatic fever. There were no clinics or hospitals in Harrison then, so mother had to nurse her at home. I spent the winter with my Uncle Riley and Grandmother Womack because mother and my two older sisters had their hands full taking care of my baby sister. There was very little that could be done for her medically, and she developed a leakage of the heart and died the following spring.

Uncle Roy had gone broke in the store business in 1931 and had started operating a company owned service station on the corner of Cherry and Stephenson arid Aunt Mittie had a little lunchroom adjoining called The Goblin's Den. This was just across the street from the high school and Central grade school, so in addition to Aunt Mittie selling hamburgers, chili, candy and school supplies in the Goblin's Den, Roy also had the concession to sell candy, popcorn, gum and soft drinks at all of the athletic events both in the gymnasium and the football field. So, he gave me the job of helping him sell from the concession stands at the ballgames. Dad was also helping Uncle Roy with the service station work, and I would also help at that part of the time, I remember that we sold hand pumped gasoline for as low-as eleven. cents per gallon, kerosene for seven cents a gallon, motor oil in bulk for ten cents a quart, flats repaired and grease jobs for a quarter and batteries charged for twenty nine cents. Business got so good for the Southland Cut Rate Station that Roy was operating, that in 1935, they decided to build another one; so they built the station that is on the right of the highway on the curve at the south end of the Krooked Kreek bridge and hired Dad to operate it for them. By this time I was in junior high school and was helping Dad in the station what time I was not in school. Dad operated the station for Southland until in 1938, when he went to work for the Arkansas Highway Department, helping to service and maintain their vehicles and road equipment. I worked about a year part time for Paul Lee, who was operating the Barnsdall service station on the corner of Stephenson and Pine Streets, when I was a sophomore in high school.

I guess you would think that I had no time for playing while I was growing up? Not so!!! We lived along the banks of Krooked Kreek, and we spent a lot of time swimming and fishing and even skating on its ice in extremely cold weather. Yoyos, tops, marbles, horseshoes, shinney, rubber guns, beanflips, hoops and tire rolling, football, baseball, and basketball and track events were all inexpensive ways of having fun and we never had any trouble of finding plenty of playmates to participate in any and all activities. Oh yes, there was also horseback riding, bicycling and tennis. I had a pony until I was eight or nine years old.

High School

During my junior and senior year in high school, I worked part time at the Coca Cola bottling plant. Ben Garrison was operating the franchise and I would work six days a week in the summer months and when school was in session, I would skip school on Friday afternoons, and we would bottle on Friday afternoons and Saturdays. I made $2 per day working at the plant and thought I had struck it rich, just to be able to work there part time.

Older brother, Eugene graduated from High School in 1934 and he had lettered every year, both in junior high and high school in football, basketball and track. He was also a good baseball player and while there was no high school baseball team, he did play on the "town team" after he graduated.' He was quite an athlete. I played a couple of years of high school basketball but never spent enough time at it to be too good.

My older sister, Edna graduated in 1936 and while it was not financially feasible for her to attend college, she served an apprenticeship and became a beautician. She later met and married Harrison Perry from Savannah, Tennessee where they later became successful in the furniture business.

My sister, Nina Maude, who is two years older than T, graduated from high school in 1938, She worked for Moore and Henley law firm as a legal secretary for about a year and also as a secretary for the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad. In 1940, she took a Civil Service examination and went to work for the War Department in Washington, D.C., where she later became personal secretary to the Under Secretary of War. Later on she also worked as a personal secretary for Senator Maybank of North Carolina, when he was Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.

In 1940, 1 graduated from high school and went to work as a fountain clerk (we called ourselves soda jerkers) for Sims' Drug Store. Since it was not possible for me to attend college, I took some commercial courses in post graduate work the following school term.

Older brother, Eugene graduated from High School in 1934 and he had lettered every year, both in junior high and high school in football, basketball and track. He was also a good baseball player and while there was no high school baseball team, he did play on the "town team" after he graduated.' He was quite an athlete. I played a couple of years of high school basketball but never spent enough time at it to be too good.

My older sister, Edna graduated in 1936 and while it was not financially feasible for her to attend college, she served an apprenticeship and became a beautician. She later met and married Harrison Perry from Savannah, Tennessee where they later became successful in the furniture business.

My sister, Nina Maude, who is two years older than T, graduated from high school in 1938, She worked for Moore and Henley law firm as a legal secretary for about a year and also as a secretary for the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad. In 1940, she took a Civil Service examination and went to work for the War Department in Washington, D.C., where she later became personal secretary to the Under Secretary of War. Later on she also worked as a personal secretary for Senator Maybank of North Carolina, when he was Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.

In 1940, 1 graduated from high school and went to work as a fountain clerk (we called ourselves soda jerkers) for Sims' Drug Store. Since it was not possible for me to attend college, I took some commercial courses in post graduate work the following school term.

Moving to DC--Working for the War Department--1941

In the spring of 1941, I took a Civil Service clerk-typist examination and as a result, received an appointment and went to work for the War Department in Washington, D.C.

It surely was nice to have my sister there to meet me and help me to find a place to live. She was living in a boarding house on New Hampshire Avenue and found me a boarding house close by her. Nina had met Ed Tull, who was from Jonesboro and a friend of Jim Langley, my high school basketball coach.. Ed, who worked for the Agriculture Department, was attending American University at night, studying for the ministry. He and Nina were engaged and were married in August of 1941. Ed was chosen to be pastor of the Brookmont, Md., Baptist Church and they moved into an apartment there. About a month later, I had the opportunity to board with Mr. and Mrs. Donaldson, who were members of Ed's church. They had a large home in Brookmont and their children had already married and left home, so Mrs. Donaldson made her occupation of running the boarding house in her home. Mr. Donaldson was a machinist at the Washington Naval Yards, and a couple of boys that worked with him were already boarding with them. I had a friend, Floyd Vaughn from Morgan City, Louisiana who had gone to work at the same time with me that moved into Donaldsons' as my roommate. We did not have an automobile but the streetcars from Washington came through Georgetown on the Cabin John Line, and we could travel anywhere in the District by streetcar. Vaughn and I both worked in the office of the Chief of Finance of the War Department. He was in the Supply branch and I was in Publications branch and both of our superiors were black men who had been with the Bureau for many years. Vaughn had attended LSU and was a reserve pilot in the ROTC reserve program. In the publications branch, it was my job to cut stencils and make mimeograph copies of Army and Finance Regulations and to mail them out to all Finance Officers in the field. We maintained a mailing list of all Finance Officers on addresso-graph plates, which we cut on grapho-type machines and would mail any new Regulation, Executive Orders or General Accounting office orders to the Finance-Officers throughout the world. I worked about six months in Publications and received a promotion to the Advisory and Regulations Division of the Bureau. In this job, I corresponded directly with the Finance Officers in the field regarding pay allowances and gratuities if the officer had questions regarding entitlement or interpretations of the regulations.

It surely was nice to have my sister there to meet me and help me to find a place to live. She was living in a boarding house on New Hampshire Avenue and found me a boarding house close by her. Nina had met Ed Tull, who was from Jonesboro and a friend of Jim Langley, my high school basketball coach.. Ed, who worked for the Agriculture Department, was attending American University at night, studying for the ministry. He and Nina were engaged and were married in August of 1941. Ed was chosen to be pastor of the Brookmont, Md., Baptist Church and they moved into an apartment there. About a month later, I had the opportunity to board with Mr. and Mrs. Donaldson, who were members of Ed's church. They had a large home in Brookmont and their children had already married and left home, so Mrs. Donaldson made her occupation of running the boarding house in her home. Mr. Donaldson was a machinist at the Washington Naval Yards, and a couple of boys that worked with him were already boarding with them. I had a friend, Floyd Vaughn from Morgan City, Louisiana who had gone to work at the same time with me that moved into Donaldsons' as my roommate. We did not have an automobile but the streetcars from Washington came through Georgetown on the Cabin John Line, and we could travel anywhere in the District by streetcar. Vaughn and I both worked in the office of the Chief of Finance of the War Department. He was in the Supply branch and I was in Publications branch and both of our superiors were black men who had been with the Bureau for many years. Vaughn had attended LSU and was a reserve pilot in the ROTC reserve program. In the publications branch, it was my job to cut stencils and make mimeograph copies of Army and Finance Regulations and to mail them out to all Finance Officers in the field. We maintained a mailing list of all Finance Officers on addresso-graph plates, which we cut on grapho-type machines and would mail any new Regulation, Executive Orders or General Accounting office orders to the Finance-Officers throughout the world. I worked about six months in Publications and received a promotion to the Advisory and Regulations Division of the Bureau. In this job, I corresponded directly with the Finance Officers in the field regarding pay allowances and gratuities if the officer had questions regarding entitlement or interpretations of the regulations.

The U.S. goes to War

On December 7, 1941, Vaughn and I attended a Sunday Matinee and when we came out of the theatre, the "extra" news editions were on the street giving the account of the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese Statesmen had been in meetings with Cordell Hull then Secretary of State during the previous week. The employees at the Japanese Embassy had carried out all papers and documents and had burned them on the Embassy lawn.

Since Floyd was in the reserve he knew that he would be called to active duty within weeks. The next day President Roosevelt met in joint session with Congress and declared War. "December 7, 1941, a day that will go down in infamy".

Sure enough, Floyd received his orders to report to Maxwell Field within just a few weeks. I corresponded with him for several months. He was attached to a B-26 training squadron and the B-26 was a relatively new twin engine bomber, shaped like a cigar, with a short wing span for its body size. In correspondence, I could tell that Floyd was concerned because he told me that it was the hottest plane he had ever climbed into and that several planes and crews had been lost in operational training. He later told me in correspondence that he had been the first pilot to land one of them on one engine, to be able to tell about it.

Since Floyd was in the reserve he knew that he would be called to active duty within weeks. The next day President Roosevelt met in joint session with Congress and declared War. "December 7, 1941, a day that will go down in infamy".

Sure enough, Floyd received his orders to report to Maxwell Field within just a few weeks. I corresponded with him for several months. He was attached to a B-26 training squadron and the B-26 was a relatively new twin engine bomber, shaped like a cigar, with a short wing span for its body size. In correspondence, I could tell that Floyd was concerned because he told me that it was the hottest plane he had ever climbed into and that several planes and crews had been lost in operational training. He later told me in correspondence that he had been the first pilot to land one of them on one engine, to be able to tell about it.

Enlisted--July, 1942

I enlisted in the Navy in July, 1942 and lost contact with Vaughn. I guess we were both just too busy after that to keep in touch. I always thought that I would check around Morgan City, Louisiana to see what might have happened to him but so far I have never been around there. I went to boot camp in Norfolk, Virginia, during July and August, 1942. While there, the U.S.S. Ranger was in port and a couple of Harrison boys with whom I had played basketball in high school were aboard her. The first liberty that I received, I went aboard to see the Watkins brothers, as well as the ship. I thought the Ranger was surely the largest ship afloat, since I had never been on anything bigger than an excursion boat. I think that was the only liberty that I made while in boot camp. I missed some hard rowboat work because they put me to work in the office typing ID cards and liberty passes.

When we finished boot camp, we received 72 hour passes and I headed for Brookmont, Md., where mother was visiting with Ed and Nina. When I reported back to Norfolk, I did not draw Yoeman's School as I thought I probably would, but instead, I was to report to RCA Radio School in New York, New York. It seems that I had an aptitude to be a radio operator, which also required the ability to type.

When we finished boot camp, we received 72 hour passes and I headed for Brookmont, Md., where mother was visiting with Ed and Nina. When I reported back to Norfolk, I did not draw Yoeman's School as I thought I probably would, but instead, I was to report to RCA Radio School in New York, New York. It seems that I had an aptitude to be a radio operator, which also required the ability to type.

Radio School--NYC--Oct.-Dec. 1942

En route to New York, we traveled on a small craft up the Chesapeake Bay to Wilmington, Delaware. From there, we traveled by truck to Pier 92 on the Hudson River. There were two old cruisers tied up at Pier 92, the Camden and the New Jersey One was used for a receiving ship and the other a prison ship. Of course, the receiving ship was too small to handle and house all the sailors that were in transit at that time and Pier 92 had been taken over in its entirety, for living quarters. So Pier 92 became my home for the next four months. The Pier was grossly overcrowded, as we were sleeping in four-decker bunks and with the eating and toilet facilities being inadequate to properly take care of that many men, it left a lot to be desired for sanitary conditions. None the less, it was not hard to realize that we were lucky to be able to live, even under those conditions, because, at that time, the North African Campaign was in full blast and many soldiers didn't have it so good. Besides, there were many good things about being in New York. There were only about 40,000 sailors around the city. We got liberty every other night. We were within walking distance of Times Square and there were plenty of places to go and things to see. The people of New York were most friendly and generous to servicemen. There were numerous USO clubs and invitations to attend private parties in private homes for-holidays and special events. We were given free passes to professional baseball and football games and some college football games.

On Halloween, some girls from the Bronx that worked at Kresge's had a private party and invited some soldiers and sailors through the USO to attend. They had hired a small dance band and everyone had an enjoyable evening. on Thanksgiving, there was an invitation extended on the bulletin board for two sailors to have dinner with a family on Park Avenue. My buddy, Smitty, from Atlanta, Georgia and I decided to accept. Of course, we did not know what to expect, but when we arrived, there were a couple of soldiers from Fort Dix, who had also accepted an invitation, already there. It was apparent that the people were well off, as they were living in a nice high rise condo. They were a nice middle-aged couple and they had a couple of daughters home from college for the holidays. The man played the guitar very capably and we spent the afternoon singing to his playing. He claimed that he had learned to play in his younger days when he was hoboing around the country, riding the rails. When it came time for dinner, they took us to the first floor of the building, where the dining room facilities were operated exclusively for the tenants of the condo. I'm not sure how they could afford it but after dinner, all of us went to Radio City Music Hall, where they had reserve choice seats for the Premier of "Random Harvest". I had not expected so much hospitality and it was a great experience for a country boy who had come to town. I was discovering that those Damn Yankees could match our southern hospitality. In the line of conversation, when the man learned that Smitty was from Atlanta, he asked him if he knew of a certain textile mill there and Smitty replied that he passed it on his way to work. The man told him that he owned the mill. Later, Smitty told me that it was one of the biggest industries in Atlanta.

I was fortunate to have two friends while in New York who were natives. Both of them were named Bill Murphy. Both were Irish and Catholic and both were from Brooklyn. Bill Murphy #1, 1 had become acquainted with in D. C. He had worked for the Army Map Service and had also boarded at Mrs. Donaldsons. He was still single and had returned to Brooklyn to accept a better job and live at home. Not only did he invite me into his home for some of his mother's home cooking but lots of times, when I would have liberty, he would go with me to eat dinner and would show me some of the more interesting places to see and would tell me of things and events of interest to see, when he could not go with me. Bill Murphy #2, was in radio school with me. His mother worked for NYC telephone company and on one of my liberties, Bill and I went through the exchange where she worked and the complexity of it was mind boggling for a country boy, at that time. Bill's mother also prepared home cooked food for us and I can still remember how good her pineapple upside down cakes tasted. I remember that on Christmas Eve , 1942, 1 attended Mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral with Bill. I was reared in the Presbyterian Church and though I attended the Baptist Church at Brookmont, this was the first Catholic service that I had ever attended. I was impressed even though there were many things about the service that I did not understand. The things that were similar did convince me that most of the differences of the different denominations of Christian Churches are insignificant. In two short years, I had moved from a rural, predominantly white Anglo-Saxon protestant society into one which was urban, with many different creeds and nationalities. The significant common denominator was the fact that they were all proud to be Americans and the majority wanted to do their fair share to contribute to the war effort. I have never seen people united behind a single cause as much as they were in World War II.

I have many memories of Pier 92 and NYC not connected with radio school. For the entire four months I was there, the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth would alternate coming into Pier 91, where they would stay in port about a week each, taking on war material, troops and supplies that were being shipped to England. It is difficult to imagine the amount of cargo that these ships were carrying on each trip. They would come into port drawing about twenty five feet of water and when they would leave they would be drawing forty to forty five feet. The day before they were to leave port, soldiers would march single file up the gangplanks all day and night. Although the German U-boats were having a field day sinking our cargo ships in the North Atlantic at that time, thank God neither of the Queens were ever hit. I also remember spending a liberty at the USO club at Yonkers, when the Swedish ship "Gripsholm" was in port. I met several of the Swedish sailors and though I didn't understand them very well, we could at least play a good game of ping pong with each other. The Gripsholm was being used to exchange diplomatic prisoners that were taken when the war was declared.

RCA Radio School had been taken over by the Navy to train shipboard radio operators. While we were primarily concerned with learning the Morse Code to the extent that we could receive messages and type them out, we were also taught a smattering of electronics and radio theory. Most of us were able to receive and type code at the rate of thirty to thirty five words per minute, upon finishing the course. We were promoted to Radioman 3C, upon graduation, and we stated our preferrences, in numerical order, for the types of duty we would like the most. I remember that my list looked something like this:

1. Submarines

2. -Aircraft

3. Aircraft Carriers

4. Battleships

5. Cruisers

6. Destroyers

7. P T Boats

Well, I guess Uncle Sam needed Aviation Radiomen more than anything else, because I received orders to report to Aviation Radio School, at Naval Air Technical Training Center, Memphis, Tennessee.

It had been most difficult for me to understand the difference in social status between officers and enlisted men. I knew it was generally a difference in education, as the college graduates were generally always officers, and if you had no college, you had to work up through the ranks.

The officers who were not liked by enlisted men were referred to in the ranks as "ninety day wonders", or, "Officers and Gentlemen by an Act of Congress". We also had the saying that "there is only one Navy, the Queens Navy", which expressed the resentment of enlisted men for the U S Navy being so closely patterned after the British Navy.

On Halloween, some girls from the Bronx that worked at Kresge's had a private party and invited some soldiers and sailors through the USO to attend. They had hired a small dance band and everyone had an enjoyable evening. on Thanksgiving, there was an invitation extended on the bulletin board for two sailors to have dinner with a family on Park Avenue. My buddy, Smitty, from Atlanta, Georgia and I decided to accept. Of course, we did not know what to expect, but when we arrived, there were a couple of soldiers from Fort Dix, who had also accepted an invitation, already there. It was apparent that the people were well off, as they were living in a nice high rise condo. They were a nice middle-aged couple and they had a couple of daughters home from college for the holidays. The man played the guitar very capably and we spent the afternoon singing to his playing. He claimed that he had learned to play in his younger days when he was hoboing around the country, riding the rails. When it came time for dinner, they took us to the first floor of the building, where the dining room facilities were operated exclusively for the tenants of the condo. I'm not sure how they could afford it but after dinner, all of us went to Radio City Music Hall, where they had reserve choice seats for the Premier of "Random Harvest". I had not expected so much hospitality and it was a great experience for a country boy who had come to town. I was discovering that those Damn Yankees could match our southern hospitality. In the line of conversation, when the man learned that Smitty was from Atlanta, he asked him if he knew of a certain textile mill there and Smitty replied that he passed it on his way to work. The man told him that he owned the mill. Later, Smitty told me that it was one of the biggest industries in Atlanta.

I was fortunate to have two friends while in New York who were natives. Both of them were named Bill Murphy. Both were Irish and Catholic and both were from Brooklyn. Bill Murphy #1, 1 had become acquainted with in D. C. He had worked for the Army Map Service and had also boarded at Mrs. Donaldsons. He was still single and had returned to Brooklyn to accept a better job and live at home. Not only did he invite me into his home for some of his mother's home cooking but lots of times, when I would have liberty, he would go with me to eat dinner and would show me some of the more interesting places to see and would tell me of things and events of interest to see, when he could not go with me. Bill Murphy #2, was in radio school with me. His mother worked for NYC telephone company and on one of my liberties, Bill and I went through the exchange where she worked and the complexity of it was mind boggling for a country boy, at that time. Bill's mother also prepared home cooked food for us and I can still remember how good her pineapple upside down cakes tasted. I remember that on Christmas Eve , 1942, 1 attended Mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral with Bill. I was reared in the Presbyterian Church and though I attended the Baptist Church at Brookmont, this was the first Catholic service that I had ever attended. I was impressed even though there were many things about the service that I did not understand. The things that were similar did convince me that most of the differences of the different denominations of Christian Churches are insignificant. In two short years, I had moved from a rural, predominantly white Anglo-Saxon protestant society into one which was urban, with many different creeds and nationalities. The significant common denominator was the fact that they were all proud to be Americans and the majority wanted to do their fair share to contribute to the war effort. I have never seen people united behind a single cause as much as they were in World War II.

I have many memories of Pier 92 and NYC not connected with radio school. For the entire four months I was there, the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth would alternate coming into Pier 91, where they would stay in port about a week each, taking on war material, troops and supplies that were being shipped to England. It is difficult to imagine the amount of cargo that these ships were carrying on each trip. They would come into port drawing about twenty five feet of water and when they would leave they would be drawing forty to forty five feet. The day before they were to leave port, soldiers would march single file up the gangplanks all day and night. Although the German U-boats were having a field day sinking our cargo ships in the North Atlantic at that time, thank God neither of the Queens were ever hit. I also remember spending a liberty at the USO club at Yonkers, when the Swedish ship "Gripsholm" was in port. I met several of the Swedish sailors and though I didn't understand them very well, we could at least play a good game of ping pong with each other. The Gripsholm was being used to exchange diplomatic prisoners that were taken when the war was declared.

RCA Radio School had been taken over by the Navy to train shipboard radio operators. While we were primarily concerned with learning the Morse Code to the extent that we could receive messages and type them out, we were also taught a smattering of electronics and radio theory. Most of us were able to receive and type code at the rate of thirty to thirty five words per minute, upon finishing the course. We were promoted to Radioman 3C, upon graduation, and we stated our preferrences, in numerical order, for the types of duty we would like the most. I remember that my list looked something like this:

1. Submarines

2. -Aircraft

3. Aircraft Carriers

4. Battleships

5. Cruisers

6. Destroyers

7. P T Boats

Well, I guess Uncle Sam needed Aviation Radiomen more than anything else, because I received orders to report to Aviation Radio School, at Naval Air Technical Training Center, Memphis, Tennessee.

It had been most difficult for me to understand the difference in social status between officers and enlisted men. I knew it was generally a difference in education, as the college graduates were generally always officers, and if you had no college, you had to work up through the ranks.

The officers who were not liked by enlisted men were referred to in the ranks as "ninety day wonders", or, "Officers and Gentlemen by an Act of Congress". We also had the saying that "there is only one Navy, the Queens Navy", which expressed the resentment of enlisted men for the U S Navy being so closely patterned after the British Navy.

Aviation School, Gunnery School--March/April, 1943

When I got to Aviation school at Memphis, I decided that "There were only two Navies, the Queen's Navy and Crump's Navy". Mr. Crump was the political boss at Memphis, and he had made his influence felt so strongly on the base at Millington, that one wondered if Millington was still part of the U S Navy. The commanding officer of the base was Captain. Norman R. Hitchcock, and probably he was the only officer on the base at that time who had been to sea. We did have some excellent enlisted instructors who had seen combat duty and they taught us a lot. The main thing we learned at Memphis was principals and operations of Radar. Up until this time, I hadn't even heard of Radar, much less to have seen a set. Radar was a highly classified subject at that time, as it was one of the Navy's secret weapons. In addition to radar, we learned ship and aircraft recognition; voice radio procedure; visual blinker reading; semaphore and more radio theory. Several of the fellows that were in school in NYC were with me at Aviation school at Memphis. We finished this school in March, 1943 and about all of us were sent on to Aerial Gunnery School in Hollywood, Florida.

The Gunnery School at Hollywood was at the edge of the city, which was also the edge of the everglades at that time. The Navy had taken over a boy's military academy and had cut the gunnery range out of the everglades. A small circular railroad track was laid for the purpose of pulling a target sleeve. We had thirty and fifty caliber machine gun mounts, stationed around the track in positions so that all of the firings were into the everglades located in the background. Each man would dip the tips of the projectiles on his belt of ammunition into a different color paint and when the target was hit, the paint color would show up on the target sleeve, thereby making it possible to score your marksmanship. We also fired many rounds with shotguns and shotguns on machine gun mounts, at clay pigeons dispensed by both skeet and trap methods. We fired many, many rounds day after day to perfect our marksmanship, motion tracking ability and to learn how to break down and clean and maintain our guns. After a months intensive training, we were all pretty fair shooters. One of the highlights of being at Hollywood was that I got to visit with brother Gene, who lived at Cape Canaveral and was a Border Patrolman patrolling the coast between Canaveral and Key West. At that time, the German U-boats were sinking many of our tankers and cargo ships along the Atlantic coast, many of them just short distances offshore. I had not seen Gene for about two years previously and we were able to get together two or three times when he would be working close to Hollywood.

Upon graduation from Aerial Gunnery School, it was normal procedure for the gunners to be sent up to Fort Lauderdale, where the Navy had an airfield that was used for operational training for new pilots and air crewmen. That was the place to go to learn squadron tactics and gain all kinds of flying experience. It just so happened that Uncle Sam was in dire need of air crewmen with the fleet, because of the heavy losses we had sustained from the battles of Midway and the Coral Sea. So, the men who were in the top ten percent of our graduating class from Hollywood were sent directly to San Diego, California to join the fleet. This included ten other men besides me, of which all of us had been together since we met at radio school in NY C. The list was as follows:

1. James M. Morris, age 21, from Derby, Virginia, who had worked as a machinist helper before enlisting.

2. James B. Gaffney, age 21, from Easton, Pa., who had been a musician and clerk in civilian life.

3. C. A. Fagan, age 18, from Dallas, Texas who was formerly a payroll clerk.

4 ' . Glen Froetschner, age 22 from Larned Kansas, a farmer and former clerk.

5. Richard F. Gentzkow, age 23, from Salem, Oregon, who had previously worked for Boeing Aircraft.

6. Ted M. Grudzien, age 21, a former college student, from Cleveland, Ohio.

7. James B. Katke, age 22, from Wanwatosa, Wisc., formerly a storekeeper for St. Paul and Pacific railroad.

8. Charles R. Paul from Piedmont, Missouri, who had worked for Montgomery Ward before enlistment.

9. James B. Steckf age 21, from Sibley, Iowa, a former student and football player for Morningside College.

10. Edward O'Conner, Jr., age 20, from El Cajon, California, formerly employed by Cudahy Packing Company.

Well, we spent six days on a troop train, four of them in Texas, between Hollywood, Florida and San Diego, California; A very tiring experience.

The Gunnery School at Hollywood was at the edge of the city, which was also the edge of the everglades at that time. The Navy had taken over a boy's military academy and had cut the gunnery range out of the everglades. A small circular railroad track was laid for the purpose of pulling a target sleeve. We had thirty and fifty caliber machine gun mounts, stationed around the track in positions so that all of the firings were into the everglades located in the background. Each man would dip the tips of the projectiles on his belt of ammunition into a different color paint and when the target was hit, the paint color would show up on the target sleeve, thereby making it possible to score your marksmanship. We also fired many rounds with shotguns and shotguns on machine gun mounts, at clay pigeons dispensed by both skeet and trap methods. We fired many, many rounds day after day to perfect our marksmanship, motion tracking ability and to learn how to break down and clean and maintain our guns. After a months intensive training, we were all pretty fair shooters. One of the highlights of being at Hollywood was that I got to visit with brother Gene, who lived at Cape Canaveral and was a Border Patrolman patrolling the coast between Canaveral and Key West. At that time, the German U-boats were sinking many of our tankers and cargo ships along the Atlantic coast, many of them just short distances offshore. I had not seen Gene for about two years previously and we were able to get together two or three times when he would be working close to Hollywood.

Upon graduation from Aerial Gunnery School, it was normal procedure for the gunners to be sent up to Fort Lauderdale, where the Navy had an airfield that was used for operational training for new pilots and air crewmen. That was the place to go to learn squadron tactics and gain all kinds of flying experience. It just so happened that Uncle Sam was in dire need of air crewmen with the fleet, because of the heavy losses we had sustained from the battles of Midway and the Coral Sea. So, the men who were in the top ten percent of our graduating class from Hollywood were sent directly to San Diego, California to join the fleet. This included ten other men besides me, of which all of us had been together since we met at radio school in NY C. The list was as follows:

1. James M. Morris, age 21, from Derby, Virginia, who had worked as a machinist helper before enlisting.

2. James B. Gaffney, age 21, from Easton, Pa., who had been a musician and clerk in civilian life.

3. C. A. Fagan, age 18, from Dallas, Texas who was formerly a payroll clerk.

4 ' . Glen Froetschner, age 22 from Larned Kansas, a farmer and former clerk.

5. Richard F. Gentzkow, age 23, from Salem, Oregon, who had previously worked for Boeing Aircraft.

6. Ted M. Grudzien, age 21, a former college student, from Cleveland, Ohio.

7. James B. Katke, age 22, from Wanwatosa, Wisc., formerly a storekeeper for St. Paul and Pacific railroad.

8. Charles R. Paul from Piedmont, Missouri, who had worked for Montgomery Ward before enlistment.

9. James B. Steckf age 21, from Sibley, Iowa, a former student and football player for Morningside College.

10. Edward O'Conner, Jr., age 20, from El Cajon, California, formerly employed by Cudahy Packing Company.

Well, we spent six days on a troop train, four of them in Texas, between Hollywood, Florida and San Diego, California; A very tiring experience.

Training with Air Group Six--Spring, 1943

When we arrived in San Diego, we were all assigned to Torpedo Squadron Six (VT-6). VT-6 was a part of Air Group Six that was just reforming. Airgroup Six had served on the old Hornet when she was sunk at the Battle of Santa Cruz and the new airgroup contained a contingency of the old airgroup, including our Airgroup Commander "Butch" O'Hare. Comdr. O'Hare had become an Ace and had received the Congressional Medal of Honor, while serving as a fighter pilot with Old VF-6 and flying the old F4F. When President Roosevelt personally awarded him the Congressional Medal, he asked him to give the specifications for a new fighter plane for the Navy and the F6F was built by Grumman according to those specifications and they were already being supplied to the fleet.

An Airgroup consisted of a full complement of men and planes that would operate off a carrier at a given time. It consisted of a Fighter Squadron (VF) containing seventy five fighter planes (F6F-s) and about one hundred fighter pilots, a Torpedo Squadron (VT) containing eighteen Torpedo Planes (TBF's or TBM's) and twenty four flight crews. A flight crew for the three place Torpedo Plane included the pilot, the turret gunner, who was usually an ordnanceman (AOM) and a radioman (ARM) that doubled as a tail gunner. And, a Bomber Squadron (VB) containing thirty six bomber planes (SB2C's) and about forty flight crews. A Bomber Plane crew was just two men, the pilot and turret gunner who was usually a radioman (ARM).

[note: this information from Merlin Dorfman--- A typical carrier air group contained 2 VF, 1 VS, 1 VB, 1 VT (18 each,total 90). The VS and VB aircraft were identical and both performed both missions (scouting and bombing) as required.

So, Air Group Six was reformed, and our Squadron (VT-6) Commander was Lt. Cmdr. Phillips, I was assigned to fly with our Radio Officer, Lt. Larue G. Buchanan who was from Syracuse, N.Y., and our turret gunner was Richard Miller, AOM 3C, from Springfield, Missouri. I will never forget the first flight that we made. I had never even been in an airplane before and the squadron made a glide bombing training flight which was a simulated attack on a sled that was towed by a PC boat off Point Loma. The pilots would drop hundred pound water bombs at the sled, after diving at a sixty degree angle from about 15,000 feet. The water bombs were dropped from around 3000 feet and when the pilots would pull out of their dives, the G's would nearly make you black out. I guess that I was too scared to get air sick on that first flight. I remember that I got cold on that flight. We only had been issued ear phones, and I didn't have on enough clothing, as the temperatures dropped drastically above six or seven thousand feet altitudes. The next day, they issued us all of our flight gear, so when we boarded the plane for takeoff, I had donned it all. Miller did not make that flight for some reason, so I climbed up into the turret to where I had a better view. Well, I guess that was a mistake, because the pilots decided to follow the leader in a tail chase. I thought that they did everything except an outside loop, and did I ever get airsick!! I just happened to have my white hat in my hip pocket and it made a very good sack in which to upchuck and throw overboard. That was the only time I ever got airsick and in retrospect that flight was mild, in comparison to some that I was to fly later. Nevertheless, I was happy to set foot on "terra-firma" after both my first flights. on one of our training missions at San Diego, a wing pulled off one of the torpedo planes and we lost a crew. I don't remember the names of the crew, as we did not keep logs or diaries at that time. I do remember that the radioman was from Helena, Arkansas and it was my first reminder that "except for the Grace of God, there go I". While we were in San Diego, I may have gone on liberty a couple of times. It was very similar to Norfolk, Virginia, in that you might as well stay on the base because if you went to town, all you could see was more sailors and more Navy.

Air Group Six went aboard the USS Prince Williams, a converted carrier in late May of 1943 to be transported to Pearl Harbor.

When we arrived at Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, they sent us to the Navy Auxiliary Air Station at Puunene , Maui, where we were to fly training missions and to await the overhaul of the USS Enterprise, which was at Bremerton, Washington. We were there for four months but the training that we went through in that interval proved to be invaluable to us later on. One of the most spectacular air shows that I have ever seen took place over Puunene Air Field. Our Air Group Commander "Butch" O'Hare, combat tested the Navy's new F6F fighter plane against the F4U Cosair which was flown by [Marine] Pappy Boyington. The dogfight was scored with gun cameras and surely exposed the strengths and weaknesses of both aircrafts and pilots. I am sure that those films are still filed away in Naval Aviation records somewhere. It was two of the best pilots and the Navy's two best fighter planes of that day in time and they both were pushing to the peak of their abilities. It was something, to see!

[note from Merlin Dorfman: The story I heard about FDR and the new fighter was that FDR asked O'Hare what was needed in the Pacific and O'Hare said "something that will get upstairs faster." The F6F was already flying by that time, but not in production or in service. If you get to O'Hare Airport in Chicago, there is an F4F on display there with pictures and stories about Butch O'Hare.]

An Airgroup consisted of a full complement of men and planes that would operate off a carrier at a given time. It consisted of a Fighter Squadron (VF) containing seventy five fighter planes (F6F-s) and about one hundred fighter pilots, a Torpedo Squadron (VT) containing eighteen Torpedo Planes (TBF's or TBM's) and twenty four flight crews. A flight crew for the three place Torpedo Plane included the pilot, the turret gunner, who was usually an ordnanceman (AOM) and a radioman (ARM) that doubled as a tail gunner. And, a Bomber Squadron (VB) containing thirty six bomber planes (SB2C's) and about forty flight crews. A Bomber Plane crew was just two men, the pilot and turret gunner who was usually a radioman (ARM).

[note: this information from Merlin Dorfman--- A typical carrier air group contained 2 VF, 1 VS, 1 VB, 1 VT (18 each,total 90). The VS and VB aircraft were identical and both performed both missions (scouting and bombing) as required.

So, Air Group Six was reformed, and our Squadron (VT-6) Commander was Lt. Cmdr. Phillips, I was assigned to fly with our Radio Officer, Lt. Larue G. Buchanan who was from Syracuse, N.Y., and our turret gunner was Richard Miller, AOM 3C, from Springfield, Missouri. I will never forget the first flight that we made. I had never even been in an airplane before and the squadron made a glide bombing training flight which was a simulated attack on a sled that was towed by a PC boat off Point Loma. The pilots would drop hundred pound water bombs at the sled, after diving at a sixty degree angle from about 15,000 feet. The water bombs were dropped from around 3000 feet and when the pilots would pull out of their dives, the G's would nearly make you black out. I guess that I was too scared to get air sick on that first flight. I remember that I got cold on that flight. We only had been issued ear phones, and I didn't have on enough clothing, as the temperatures dropped drastically above six or seven thousand feet altitudes. The next day, they issued us all of our flight gear, so when we boarded the plane for takeoff, I had donned it all. Miller did not make that flight for some reason, so I climbed up into the turret to where I had a better view. Well, I guess that was a mistake, because the pilots decided to follow the leader in a tail chase. I thought that they did everything except an outside loop, and did I ever get airsick!! I just happened to have my white hat in my hip pocket and it made a very good sack in which to upchuck and throw overboard. That was the only time I ever got airsick and in retrospect that flight was mild, in comparison to some that I was to fly later. Nevertheless, I was happy to set foot on "terra-firma" after both my first flights. on one of our training missions at San Diego, a wing pulled off one of the torpedo planes and we lost a crew. I don't remember the names of the crew, as we did not keep logs or diaries at that time. I do remember that the radioman was from Helena, Arkansas and it was my first reminder that "except for the Grace of God, there go I". While we were in San Diego, I may have gone on liberty a couple of times. It was very similar to Norfolk, Virginia, in that you might as well stay on the base because if you went to town, all you could see was more sailors and more Navy.

Air Group Six went aboard the USS Prince Williams, a converted carrier in late May of 1943 to be transported to Pearl Harbor.

When we arrived at Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, they sent us to the Navy Auxiliary Air Station at Puunene , Maui, where we were to fly training missions and to await the overhaul of the USS Enterprise, which was at Bremerton, Washington. We were there for four months but the training that we went through in that interval proved to be invaluable to us later on. One of the most spectacular air shows that I have ever seen took place over Puunene Air Field. Our Air Group Commander "Butch" O'Hare, combat tested the Navy's new F6F fighter plane against the F4U Cosair which was flown by [Marine] Pappy Boyington. The dogfight was scored with gun cameras and surely exposed the strengths and weaknesses of both aircrafts and pilots. I am sure that those films are still filed away in Naval Aviation records somewhere. It was two of the best pilots and the Navy's two best fighter planes of that day in time and they both were pushing to the peak of their abilities. It was something, to see!

[note from Merlin Dorfman: The story I heard about FDR and the new fighter was that FDR asked O'Hare what was needed in the Pacific and O'Hare said "something that will get upstairs faster." The F6F was already flying by that time, but not in production or in service. If you get to O'Hare Airport in Chicago, there is an F4F on display there with pictures and stories about Butch O'Hare.]

Ed's Note--Dates

You'll see that the recollections for the remainder of the war are detailed with more specific dates. As Dad notes, he was able to keep his own logbook from this point in his service, so he has more specific details regarding the missions and their dates.

I've been scanning Dad's logbook, and will try to link them to specific dates--but this might take a bit of time. Come back again if this is of interest to you.

I've been scanning Dad's logbook, and will try to link them to specific dates--but this might take a bit of time. Come back again if this is of interest to you.

The Enterprise--Nov-Dec. 1943--The Gilbert Islands

The Enterprise arrived on the scene in November and we went aboard her to join Task Force 58. Thanksgiving Day of 1943 was observed on the Enterprise as we were en route to the Gilbert Islands. Task Force 58 and Task Force 38 were exactly the same ships. When Admirals Mitcher and McCain were in, command it was task force 58, and when Admirals Halsey and Spruance were in command it was task force 38, Since they were alternating commands monthly, I'm sure the Japanese thought that we had two separate Task Forces.

[note from Merlin Dorfman: TF 58, TF 38 etc.: As he says, they were the same ships and crews. They were part of the Fifth Fleet and the Third Fleet respectively. When Spruance was Fleet co sawmmander, it was the Fifth Fleet; Halsey, the Third Fleet. Spruance had it from its formation, 4/26/44 (previously Central Pacific Force) through the invasions of the Gilberts, Marshalls, and Marianas, until about 10/1/44 before the invasion of the Philippines when Halsey took over. Spruance got it back before Iwo Jima (January 1945) and Halsey again about 5/15/44 during the battle for Okinawa and for the restof the war. The Fast Carrier force was Task Force 58 or 38 depending on the fleet number; the invasion fleet was TF 51. (Halsey never actually commanded an invasion during this period; for the Philippines, MacArthur had the invasion force and Halsey had only the combat force, so there was never a TF 31.) Mitscher was the commander of TF 58 and of TF 38 during Halsey's first command of the Third Fleet; during the second, McCain (grandfather of the Senator) commanded TF 38. (Subdivisions of Task Forces were called Task Groups, e.g., TG 58.1 would usually be four carriers and their escorts.) The Seventh Fleet was MacArthur's navy; the USS Pennsylvania during the period of the Gilberts and Marshalls invasions was the flagship of TF 51 (commanded by Kelly Turner), part of the Fifth Fleet.]

[note from Ed: After a visit to the Intrepid museum in New York in 2023, Randy and I learned that Butch O'Hare was lost in this engagement, flying off of the Enterprise, in this engagement, rather than, as Dad reports, off of the Intrepid at Truk. See next chapter While Dad's memory of the event was essentially intact 45 years later, when he wrote this memoir, his timing was a bit off]

We started bombing and strafing the Gilberts in the last week of November, at least a week before the invasion. Air Group Six flew most of its missions on Makin Island and the air group records showed that I flew four bombing missions on that island. our bombing attacks would start at 16 or 18 thousand feet and our bombs were released at about 3000 feet. I should explain that the TBF was used as both a torpedo plane and as a bomber. When we were hitting shore installations, we used bombs and when we hit shipping, we carried torpedoes. The bomb bay had 12 bomb shackles and we could carry either a two thousand pound torpedo or a two thousand pound bomb or four 500 pound bombs or 2 one thousand pound bombs or 12 one hundred pound bombs. Of course, our loads varied with the targets that we were striking. After we would pound the islands by air for four or five days, the battleships and cruisers and destroyers would move in close enough to shell the shore with the big shipboard guns. I flew two missions with our skipper, Lt. Cmdr. Phillips. They were not considered combat missions because we flew over our own 7th fleet. The 7th fleet was composed of the older men of war of the US Navy and the transports and landing craft carrying the invasion forces. Since we had pounded the Gilberts for a week or longer before the invasion, all of the aerial photos that were taken by the Fifth Fleet ( Task Force 58) to assess the results of our bombing and shelling were bundled up for delivery to the 7th fleet, in order to assist the ground forces in the invasion of the islands. I guess the skipper asked me to assist him in the delivery of these photos, because I had had a lot of experience in pulling target sleeves for gunnery training while we were in training and the principal of delivery was essentially the same. We placed the photos in a section of fire hose five to ten feet long and used 200 feet of half inch rope and tied the fire hose in the center of the line. By tying a small sand bag to the leading end of the rope, we could dispense the rope out of the tail cone of the plane through a flare tube so that release could be made, in order to drop the pictures on another ship. of course, the pictures in the fire hose were sealed in by corking the ends of the fire hose. When we flew over the bow of the USS Pennsylvania, the flagship of the 7th fleet, we released the rope and the sailors aboard the Pensy retrieved the photos as we had made a perfect drop.

The skipper's turret gunner was Richard Boone (AOM 2c), who later became the actor of "Paladin" [Have Gun Will Travel] fame.

From the way we had pounded the islands, you would have thought that our landing forces could have walked ashore without any resistance. Not so, because the First Marine Division and one of our Carrier Aircraft Service Units that was making the landing, both sustained extremely heavy losses on D Day. The only mishap that our squadron suffered was the fact that one of our most seasoned pilots made the error of dropping his bombs on the wrong target one day while supporting the landing forces. He dropped into a tank trap that had already been occupied by our own forces and killed several of our own soldiers. I can't remember the pilot's name but the radioman was Gentzkow and the gunner's name was J. A. Green. The entire squadron felt bad about the loss of our own men and that pilot hurt more than anyone else. Oh yes, we did have one other mishap. James B Steck ARM 2 from Sibley, Iowa flew with Lt. McEnernie, an old SBD pilot who had previously flown with Lt. Buchanan. The tatk force would keep one torpedo plane in the air at all times during the daylight hours, flying anti-submarine patrol. These planes would be loaded with depth charges to be dropped on any enemy submarine that might be spotted. Lt. McEnernie and Steck and the gunner ( I can't recall his name) took off at daylight one morning and had flown the four hour anti-sub patrol and when they started to land back aboard, the LSO (landing signal officer) gave them a wave off and when the pilot hit the throttle, the engine died and they were forced to make a water landing. They all three cleared the plane and had inflated their lifejackets and were awaiting a destroyer to pick them up when the depth charges on the sinking torpedo plane exploded. The explosion did not hurt Lt. McEnernie or the gunner but it perforated Steck's lower intestinal tract. The destroyer picked up all of them and McEnernie and the gunner came back aboard the Enterprise but Steck was sent back to Pearl Harbor to the Navy Hospital. The Enterprise and Air Group Six returned to Pearl Harbor after the Gilberts had been secured in early December. I visited Steck at the Naval Hospital and the doctor's had already operated on him twice and he had lost half his body weight. For a two hundred pound football player that was a lot.

Dec. 1943-Feb. 1944---The Intrepid--The Marshall Islands, Truk

The first week we were back to Pearl, the entire squadron moved into the Royal Hawaiian Hotel for a weeks R and R ( rest and recreation). The Navy had reserved the entire hotel for the duration and it was being used for R and R for Navy personnel returning from the combat zones. It was a nice week of easy living ( most of the time on the beach and in the beer garden) but after our week was up, we moved out to NAS, Barber's Point where we spent Christmas day of 1943. We learned that the USS Intrepid had just arrived at Ford Island with Air Group Eight aboard and that we were to exchange ships with them. New Years day caught us on the Intrepid en route to the Marshall Islands with the Enterprise and Air Group Eight, plus the Saratoga and the Essex and the rest of Task Force 38.

When we arrived at the Marshalls, it was pretty much a repeat of the invasion of the Gilberts. We bombed the islands for three consecutive days. Lt. Buchanan, Miller and I flew three missions on the islands of Roi and Namur and again the escort ships moved in close and shelled the shores. And, again, the skipper asked me to fly with him to drop the aerial photos on the Pennsylvania, the Flagship of the Seventh Fleet for the landing forces that were coming in for the invasion.

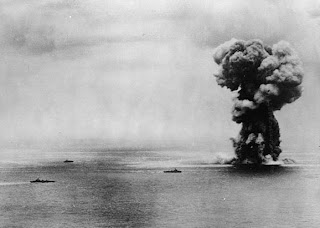

After the invasion landing was made, Task Force 38 pulled away and headed for Truk in the Caroline Islands, hoping to find and engage the Japanese Fleet. We knew that Truk was the Japanese equivalent of our Pearl Harbor, as it was their most heavily fortified fleet anchorage away from the mainland. When we arrived within striking range of Truk, it was February 16, 1944 and our crew was scheduled for the initial dawn attack on the island. Of the twelve torpedo planes from our air group, six planes would carry two thousand pound armor piercing bombs and six would carry incendiary bombs and fragment bombs. Our crew was loaded with incendiary and frag bombs and our target was gasoline storage tanks located at a sea plane base in Truk Lagoon. The incendiary bombs were about 30 inches long and 2 inches square. They were aluminum housed and contained phosphorous and other inflammable materials and they were in clusters of nine, with one cluster to the bomb shackle. The fragment bombs were about four inches in diameter and 18 inches long and were in clusters of 4 to the bomb shackle. They were impact bombs with fuses (impact fuses) in their nose. So we had 6 clusters of incendiary and 6 clusters of frag bombs on our 12 bomb shackles.